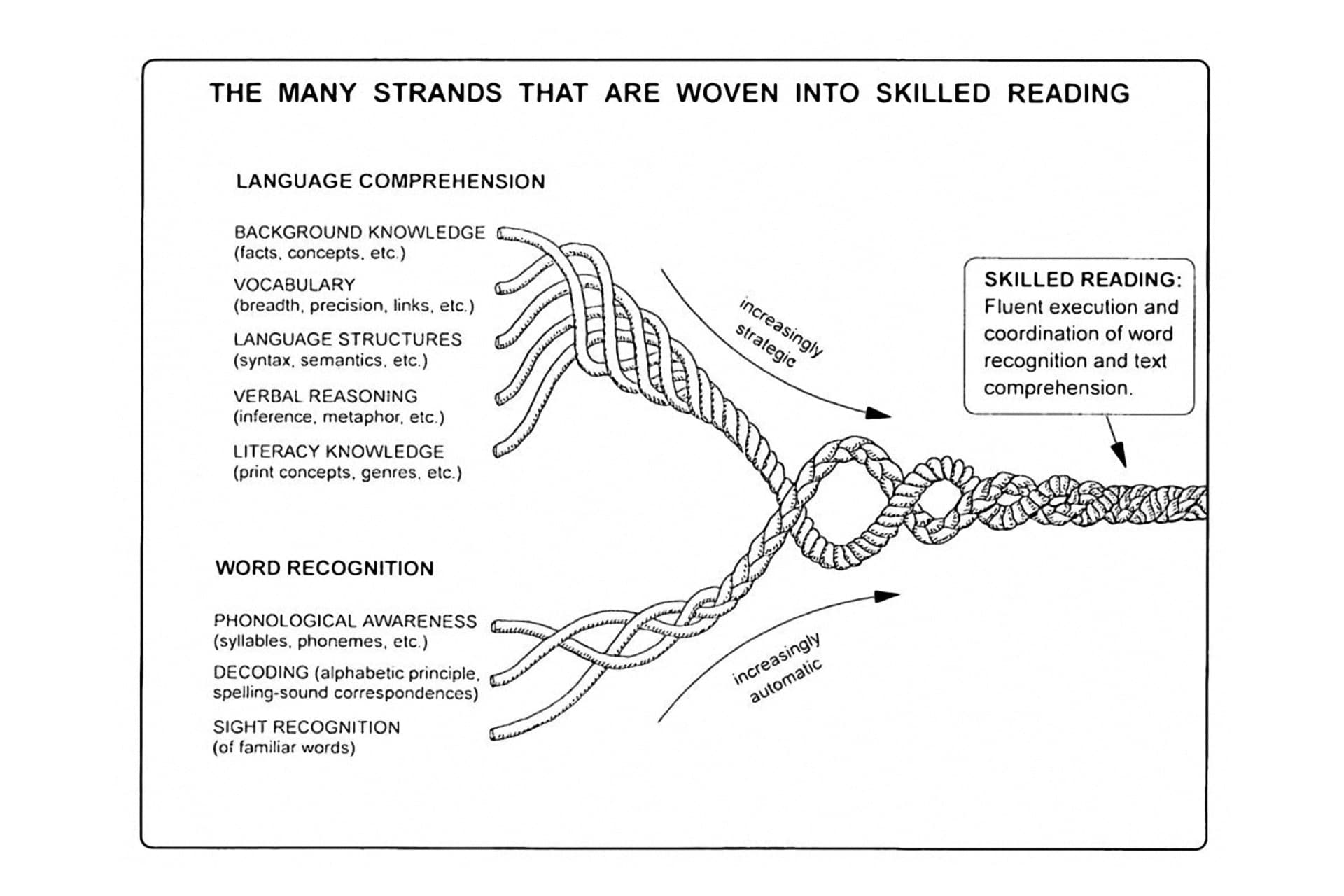

Scarborough’s Rope Model of Reading

The Rope Model (pictured above) unravels the skills involved in becoming a proficient reader and can be used to identify ways that you can assist your child as they learn to read. The rope is shown as an intertwining of 2 braided cords; both braided cords (Language Comprehension and Word Recognition) are made up of several individual strands.

As a parent, you are ideally situated to assist your child with the Language Comprehension (Upper) Cord. Your main role with the Word Recognition (lower) cord is to ensure that the schooling you choose for your child explicitly and systematically addresses these three Word Recognition strands.

The lower cord: Word Recognition

Effective reading instruction must include developing a student’s

a) awareness of the sounds in words,

b) knowledge of how these sounds are encoded and decoded by the alphabet, and

c) automaticity with frequently occurring words, and especially with those whose spelling patterns are irregular.

The Orton‑Gillingham Practical Linguistics Program at Claremont School addresses all three of these strands with a highly systematic program that is delivered by trained teachers.

The upper cord: Language Comprehension

Your child’s schooling should also include the strands shown in the Language Comprehension strand; additionally however, as parent, you play a crucial and significant role in helping your child acquire and develop the language comprehension skills that are necessary for readers to read with fluency and understanding, to read for learning and pleasure.

1) Background knowledge

Imagine you are being asked to read something about a topic that you have little to no knowledge of – 11th century poetic devices or theoretical quantum physics for example. Imagine how demanding that reading task could feel. Imagine how distracted your brain could become and how challenging it would be to stick with the text and absorb its meaning.

Readers rely on background knowledge to attend to and make sense of what they are reading. When a reader has background knowledge of a subject to draw on, they are more likely to find the text more interesting, easier to remain focused on, and less taxing on their hard-working brains. This is especially important for readers who are still relying heavily on word decoding rather than rapid word recognition. The more knowledge they have about a variety of subjects, topics and ideas, the more likely they will be able to make sense of what they are reading, and the more likely they will add to their body of knowledge.

2) Vocabulary

Perhaps you will remember reading Shakespeare as a student and finding the words and phrases being used particularly challenging to read and understand. If this was the case, how challenging was it to understand or appreciate the plot, themes or humour of these plays?

Similar to background knowledge, an extensive and rich vocabulary enables readers to make sense of what they are reading. Being able to decode words is one thing; being able to match that string of sounds to a thought, idea or concept is another. The richer a reader’s listening and spoken vocabulary, the easier they will find it to read through texts that contain words they have not seen before. If the student can use their growing decoding skills and match their result with a word they already know the meaning of, they will be more confident with their abilities and spend less overall effort on reading a text. Also, there is a greater chance that they will store the way this word looks on a page and will likely be able to access it more easily the next time they come across it.

3) Language Structures (syntax, semantics…)

Syntax is the arrangement of words in a phrase or sentence. The English language has patterns and rules to the way we order our words. It also has some flexibility and variety in acceptable patterns, and even then, speakers and writers are allowed some leeway with these patterns.

Of Yoda from Star Wars you should think! Although Yoda’s speech pattern is unique, his meaning is generally understood by those who have experience with varied syntax structures.

Children acquire varied syntax structures over time, through meaningful exposure to, and discussion of, language being spoken, read to them and presented to them in text. The greater and richer the exposure, the better they will be able to read and understand texts they are reading.

4) Verbal Reasoning (inference, metaphor…)

Reading is not restricted to merely decoding and comprehending the words on a page. More often than not, just as in spoken language, the reader must look beyond to the words to infer meaning from what is being said, what is not being said and how it is being said (or not said). A reader must be able to grasp when words are being used literally or figuratively. For instance, a reader must use verbal reasoning skills to understand that “the supermarket was a zoo” likely means that the supermarket was like a zoo because it was noisy, chaotic and crowded and not that it actually was a zoo. In a similar vein, we often use words as part of an idiomatic phrase; you may be familiar with the Amelia Bedelia children’s books and her infamous literal interpretations of commands given to her (dressing the turkey, drawing the curtains…). By talking with your child about the meaning of words, phrases, tones of voice and even body language, and about what they are observing in the world, (current events, social interactions, books you are reading together etc) you are helping your child develop and practice their verbal reasoning skills.

5) Literary Knowledge (print concepts, stories…)

A wide exposure to a variety of literary styles gives students a more developed framework on which they can rely as they read more and more for themselves. The same is true for being exposed to a variety of stories, stories with different themes, from different cultures and for different purposes. When a student is able to connect something they are reading to a story/text/theme/purpose they have already internalized, they will be better able to understand and stick with it through challenges.

What you can do

As much as you are able, give your child opportunities to learn about and appreciate a variety of subjects, topics, stories and literary styles in ways that work for them:

- read to them, from a variety of sources (books, newspapers, poems, scripts, instructions, recipes…)

- listen to radio programs or watch documentaries with them

- take them to museums, observatories, wildlife sanctuaries

- go on guided tours

- discuss your interests with your child

- introduce them to interesting people with varied interests

As appropriate:

- spend family time playing games such as “Balderdash”, “Taboo” or “Scattegories” with your child.

- discuss interesting words that come up in conversations, books, audio and video programs.

- rephrase sentences your child (or someone else) uses, “dressing them up” with interesting synonyms (or “dressing them down” with less interesting ones!)

- play with different sentence structures in fun ways during everyday conversations “To bed go you must!”